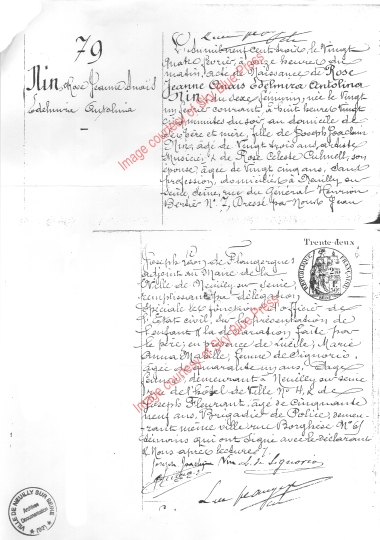

- A copy of Anais Nin’s birth certificate.

On February 24, 1903, at 11 in the morning, this birth certificate was drawn up in Neuilly sur Seine. In it, we learn that Rose Jeanne Anaïs Edelmira Antolina Nin was born at 8:25, the evening of February 21, 1903, to father Joseph Joachim Nin, 23 years old, and to mother Rose Celeste Culmell, 25 years old, at their home on 7, rue du Général Henrion Bertier, Neuilly sur Seine. The midwife was Lucile Marie Anna Mabille, 41 years old. (The spellings of the names reflect the French versions of the Spanish names.)

Interestingly, Rosa’s age is incorrect: she was in fact 31 at this time. Whether this is a clerical error or whether Joaquín and/or Rosa wanted to keep their age difference a secret is pure speculation.

According to Nin biographer Deirdre Bair, Joaquín was not pleased at having a child so early on in his marriage and, perhaps more importantly, his career. He became jealous of the attention Rosa gave her delicate daughter. This seemed to interfere with the performance relationship the couple had…at first Joaquín insisted Rosa perform with him in order to get her away from Anaïs, and then, irrationally, insisted she not perform when he felt Rosa was neglecting both him and Anaïs. From that point forward, Joaquín Nin became a solo performer and Rosa was reduced to a mother who sat in the audience to cheer him.

By the time Anaïs’s brother, Thorvald, was born in Havana in 1905, she was afflicted with typhoid fever, becoming violently ill. Joaquín was repulsed by the sight of his now very thin, sickly daughter and made sure she knew how ugly he found her. By the time Anaïs’s youngest brother, Joaquín, was born in Berlin, the family life had deteriorated to the point of chaos and violence. Beatings were brutal and often, at the hand of the father. The violence between Joaquín Sr. and Rosa intensified to the point where Anaïs feared for her mother’s life (see the introduction to “Prelude to a Symphony—Letters between a father and daughter,” A Café in Space, Vol. 6). By 1913, the family as Anaïs knew it was destroyed when her father abandoned them, and for the rest of her life she would be torn by the loss.

It is also interesting to note that while we readily celebrate Anaïs’s birthday, she rarely refers to it—or to Christmas, New Year’s Eve, or other traditionally notable days—in her adult diary. On Feb. 20, 1925, just before her 22nd birthday, she wrote: “On the eve of my birthday and bowing to tradition, I try to consider thoughtfully the significance of this venerable day—in vain. Dates never agree with my transformations. My real birthday this year was when I read Edith Wharton’s books. My New Year began when I succeeded in having my story run smoothly, when I found a renewed interest in my second book. My holidays are many—every time I go downtown with Hugh, when the agitation of the city, like the quick rhythm of some Spanish danza, makes my heart beat faster. My religious festivals fall on whatever day the sun shines—those are my Mass-going days, when I can pray.”

If you have thoughts to share on this day, Anaïs Nin’s 106th birthday, leave a comment or visit our guestbook.

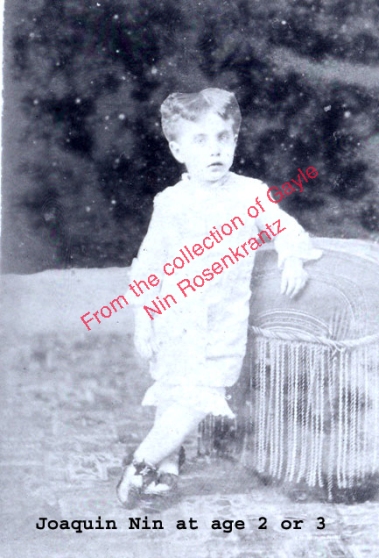

Here are some details about Anaïs Nin’s Spanish and Cuban relatives. Again, many thanks to Gayle Nin Rosenkrantz, who has cleared up some misinformation and supplied the photo.

Here are some details about Anaïs Nin’s Spanish and Cuban relatives. Again, many thanks to Gayle Nin Rosenkrantz, who has cleared up some misinformation and supplied the photo.