When Noel Riley Fitch’s study of Nin (Anaïs: The Erotic Life of Anaïs Nin) was published in 1993, the response of some in the Nin community was to swiftly brand it as “baseless” (in the sense Fitch did not have access to the Nin archive) and “sensationalistic” (in the sense it focused mainly on Nin’s love life). For the next two years, however, there were high hopes for the “official” biography, Deirdre Bair’s Anaïs Nin: A Biography, which was to be released in March of 1995. However, ominous rumblings arose even before its publication: Rupert Pole, in a letter to a friend, said the book was a “betrayal.” Gunther Stuhlmann said in a phone conversation that he had demanded his name be removed from the acknowledgements page. Once the book was published, the outcry grew, exacerbated by the response of the book reviewers, who often seemed more intent on reviewing Nin’s life rather than the biography itself.

For example, Carlin Romano of the Philadelphia Inquirer began his review with this statement: “Anaïs Nin lied and fornicated the way the rest of us breathe: regularly in order to live, and in deep gulps in order to flourish.” Nigella Lawson of The Times said: “An affair with Henry Miller—who matched [Nin] for self-centredness, grabbiness, and lack of talent…” Bruce Bawer of the New York Times said in response to Bair’s conclusion that “Nin was among the pioneers who explored three of the most important [concepts that brought sweeping societal change]: sex, the self and psychoanalysis” by retorting, “If Nin is remembered at all, it will not be as a pioneer but as a colorful peripheral character who embodied, in an extreme form, some of the more unfortunate distinguishing characteristics of our age: an obsession with fame; a zeal for self-advertisement; a tendency to confuse art and self-expression; a rejection of intellect in favor of feeling; a romantic glorification of neurosis, selfishness and irresponsibility.” The question begs to be asked: did the biography cause the responses, or did the pre-formed opinions of the reviewers and those in the Nin world skew their responses to the biography?

Within the Nin community, much was made of the fact Bair did not know Anaïs Nin personally and that she was “judgmental” in the treatment of her subject. Gunther Stuhlmann, in his introduction to Anaïs Nin: A Book of Mirrors (Sky Blue Press, 1996), addressed these issues in reaction to both Fitch’s and Bair’s books:

“In recent years a number of biographers, here and abroad, have tried to assemble their own images of Anaïs Nin. They seem to have been enthralled, most of all, by what they could glean of the erotic aspect of their moving target. With lipsmacking glee, or sour disapproval, they have turned their spotlights upon the supposedly “sensational” and “shocking” details of the private sexual life of the lady from Neuilly which, of course, fail to reveal a complete image of a complex personality, or to illuminate the nature of the impact her creations have had on a vast multi-generational audience.

“Biographers, especially when they have no personal knowledge of their subject, rely for their interpretations upon the sometimes dubious documentation of fragmented memory shards, the recollections of contemporaries often shaped by their own agendas, and most of all on the paper trail of the vanished person, the raw material of records and writings left behind.”

During the five years Deirdre Bair spent writing her biography of Anaïs Nin, she acknowledged that not having known Nin was a detriment. In her introduction, she says: “I had to settle for the verbal testimony of those who had known her…and I was astonished at the range of their responses, especially how, in so many cases, the mere mention of her name provoked vehemence and outrage… So a crucial issue became my trying to understand what there was about Anaïs Nin that made people react so strongly even though she had died more than a decade earlier.” So, were the “facts” again distorted by emotional responses to Nin? And how does one choose one response over the next as validation for factual information? And would knowing Anaïs Nin have helped in the end? To whom did she reveal her entire self during her lifetime?

In a recent interview, Bair said, “Any major event or happening or actions in Anaïs’s life began from what she wrote in her diaries at UCLA. If I wrote about something, it was because I fact-checked as thoroughly as I could. If she said she had an affair with somebody, if that person was still alive, I called them, I contacted them, I went to see them, and I asked, ‘Did you have an affair with Anaïs Nin?’ If I wrote about a possible incestuous relationship, it was because I checked every possible document, every possible person that I could. I think that was about as close to the truth as we were going to get.”

Explaining the issue of incest further, Bair says:

“The way I dealt with that was to photocopy those pages in the diary. I am a member of a group called the New York Institute for the Humanities, an NYU-affiliated body of public intellectuals, as we are called. Among them were some distinguished psychoanalysts and writers in that field—Jessica Benjamin, Muriel Dimen, Virginia Goldner, Sue Shapiro, and many of them specialize in the abuse of women. So I said to them, ‘I’m going to convene a special seminar.’ There were six analysts in total in the room. I said, ‘I’m going to pass out these photocopied pages from this diary that Anaïs Nin wrote, and at the end of the evening you have to give them back to me, and you have to swear secrecy to not tell anyone about this because I don’t know if it’s true, and I don’t know if I’m going to write it.’ So these six highly respected, important authorities in the field, they all turned to me and said, ‘It’s as if she is in my consulting room and that she’s one of my patients. This is the story that I hear.’ They called it adult onset incest. They said that often, when a parent and a child have been separated at a very young age, when they come together as adults, they see the reflection of themselves in the other and a love affair results. Shortly thereafter, a woman named Kathryn Harrison wrote just such a memoir, about her incestuous affair with her own father…it was word for word what Anaïs wrote in the diary. At that point, I knew I had to write it.

“So I said to Joaquin [Nin-Culmell], ‘I’m very, very worried. You have become a dear friend of mine, and I’m going to have to write this, and I’m afraid it’s going to end our friendship.’ And he thought very carefully for a long while. And he said, ‘Well, you’ve told me every terrible thing I’ve long suspected about my sister, but I know that you’re going to write it in such a way that you will still allow me to love her.’ And I burst into tears.”

Contrary to the reaction of Pole, Stuhlmann, and others in the inner Nin circle, both Joaquín Nin-Culmell and Gayle Nin Rosenkrantz (Nin’s brother and niece and her closest living relatives at the time) found the Bair biography to be sensitive and fair. Gayle said recently, “The problem with some is that they will say, ‘If I understand Anaïs Nin and you disagree with me, then you don’t understand her.’ Deirdre Bair didn’t paint a gallant, romantic picture of Anaïs, but overall I thought she did a very professional and sympathetic job. Perhaps Rupert felt upset because the book did not whitewash Anaïs’s life and did not sanctify his role in it.”

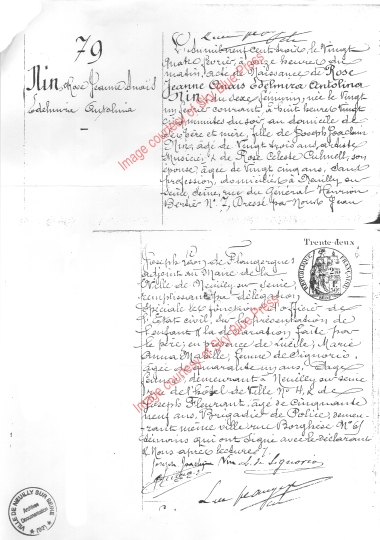

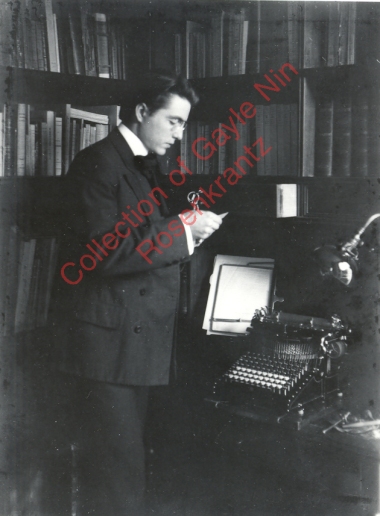

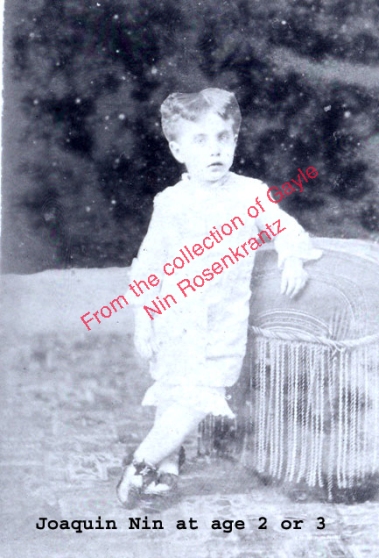

Here are some details about Anaïs Nin’s Spanish and Cuban relatives. Again, many thanks to Gayle Nin Rosenkrantz, who has cleared up some misinformation and supplied the photo.

Here are some details about Anaïs Nin’s Spanish and Cuban relatives. Again, many thanks to Gayle Nin Rosenkrantz, who has cleared up some misinformation and supplied the photo.