Both A Café in Space, Vol. 6 and Anaïs Nin Character Dictionary and Index to Diary Excerpts are now available for shipping. All of you who have ordered either or both titles will be receiving yours very soon.

Archive for the 'A Cafe in Space' Category

Café 6 and Anaïs Nin Character Dictionary are here!

March 17, 2009Interpreting Anaïs Nin’s Erotica: do we see it as we are?

March 6, 2009If there is any consensus about reading Anaïs Nin, it is that one sees aspects of one’s self in the work—whether it be fiction or the diary. Nin’s work is a mirror of sorts, and sometimes a distorted one. This is what makes Nin’s writing “personal,” and therefore “universal,” and is also a reason why there are so many disagreements about its meaning. A reader with a feminist point of view will see the feminism, and another will see something else entirely, and we haven’t even gotten into gender differences.

And about the erotica: one reason it has seen so little serious academic criticism is that it is generally believed that she knocked these stories off in her spare time with little thought or care at a buck a page for a collector, and then, near the end of her life, “sold out” by having them published. In his article “Claiming Ownership: Issues in Nin criticism—the diary vs. the fiction” (from A Café in Space, Vol. 6), Bruce Watson notes that “In his review of Nin criticism, Anaïs Nin and Her Critics, [Philip K.] Jason gives the Erotica a scant page of attention, prefaced by the dunning statement that: ‘Delta of Venus (1977) and Little Birds (1979) add little to Nin’s stature, even though they sold amazingly well…’ Jason’s tart commentary on Nin’s Erotica seems the stock critique of the seasoned academic when faced with popular literature; he seems to distrust it for the very fact that it is popular.”

However, today there is a growing trend to look critically at the erotica and to write about it. In fact, there are three articles that address Nin’s erotica in the current A Café in Space.

In her article “A ‘Clanging Cymbal—The Story of Anaїs Nin’s Reception,” Sarah Burghauser points out that “We […] know, and understand why some folks have a problem with [Nin]: but they oftentimes can’t see beyond their own ideas of what a woman writer should be and what sort of work she should produce.” Burghauser illustrates this idea with critic Edmund Miller’s take on Nin’s erotica: “[Miller argues] that Nin’s erotica does not work well as either fiction or erotica, saying, ‘Their [the stories] tendency to thwart arousal is partly a consequence of the loose plotting, but may have derived in part as well from a feminine misunderstanding of what works to arouse men.’ In this passage, Miller is complaining not only on the book collector’s behalf (as per his protest to poetry) but also on his own.”

One could claim that Edmund Miller is misinterpreting the erotica, but it could be that he is merely viewing it through his own prism—this is one of the reasons that criticizing Nin’s erotica specifically, and Nin’s work generally, has rarely been a unifying endeavor. If there are a dozen Nin readers, there will be nearly a dozen interpretations. The good news is that the erotica is finally getting the attention it deserves: as valued fiction, as groundbreaking women’s writing, and as a form of feminism, all valid considerations, and all debatable.

Anaïs Nin Myth of the Day

March 3, 2009Myth #5: Anaïs Nin’s erotica disqualifies her as any sort of feminist.

In the February issue of Glamour, there is an article entitled “6 Crazy Sex Requests Women Just Like You Have Heard.” One of the requests, reported by a 32-year-old woman was, “My husband asked, ‘Can we do it, but can it just be all about me?’ It gets better: He said I could keep the TV on so I wouldn’t miss The Office” (Glamour, p. 100). On the Smoking Gun website, there is a “Contract of Wifely Expectations” in which a man lists requirements his wife must fulfill, which, it could be argued, are repressive to say the least. Both these articles reveal that for some men, patriarchy is alive and well.

As shown in the article “Feminist Smut(?)—A study of Anaïs Nin’s erotica,” by Angela Carter in A Café in Space, Vol. 6, patriarchy is a thread running through Anaïs Nin’s erotica (Delta of Venus and Little Birds). For example, Carter uses a story from Little Birds to illustrate that Nin wrote of women’s struggle for sexual liberation in a time of patriarchal mores:

When read in the context of feminist criticism, “Hilda and Rango” is in many ways one of Nin’s more troubling stories. The reader sees the story’s protagonist struggle because her sexual actions are not socially acceptable for women. As the story unfolds, Hilda becomes more and more sexually passive in order to please a male lover who subscribes to conventional gender roles. When the story ends as Hilda submits passively to a dominant male lover, it is easy to assume, mistakenly, that Nin is sustaining gendered traditionalism. (A Café in Space, Vol. 6, p.97)

The story is based on actual events between Nin and Gonzalo More, the Peruvian who swept her off her feet in Paris in the late 30s. Despite his apparent bohemianism, More was very traditional in that he felt women should be submissive and allow the man to “have his way.” Before meeting More, Nin had been sexually awakened in her relationship with Henry Miller, who allowed her to be bold and daring. “Hilda and Rango” parallels this duality: the natural desire to be sexually adventurous and the social pressure to be passive.

Nin writes that when Hilda makes an advance on Rango, he suddenly “pushed her away as if she had wounded him” and tells her that she “made the gesture of a whore.” The story ends with Hilda submitting completely to Rango, denying her own sexuality in favor of his. Carter goes on to say:

Her will was her desire to initiate sex and Rango drove it out of her. He now rules her sexuality by denying it and forcing her to lay almost corpse-like while he teases her. In the last candlelit moment, he leads their intercourse like the demon she first saw in him. Sadly, this moment when Hilda’s idealized dream of passivity comes true is instead Rango’s moment, “his desire, his hour” (Little Birds 120). The moment that should have fulfilled the passive Hilda’s dream is not her moment at all. By leaving Hilda’s sexuality completely out of the story’s conclusion, Nin provokes the reader to question what happened to her desire, her hour. (A Café in Space, Vol. 6, p. 102)

Carter shows us that Nin indeed used her erotica to highlight the suppression of female sexuality. While Nin was never a second wave feminist in the true sense of the term, her erotica could be viewed as feminist since it expresses the struggle of women to be sexually liberated in the early 1940s, long before second wave feminism took root.

Do you have an Anaïs Nin myth you would like addressed? Let us know by e-mailing us.

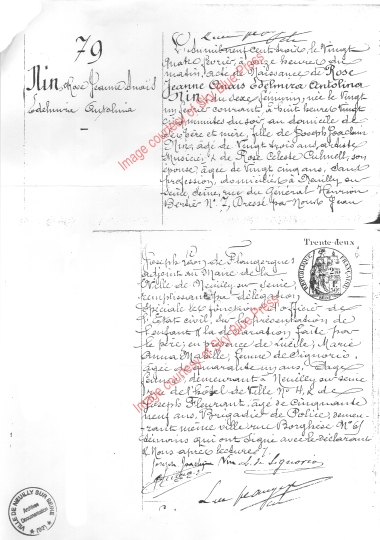

Anaïs Nin’s 106th birthday: The birth certificate

February 20, 2009

- A copy of Anais Nin’s birth certificate.

On February 24, 1903, at 11 in the morning, this birth certificate was drawn up in Neuilly sur Seine. In it, we learn that Rose Jeanne Anaïs Edelmira Antolina Nin was born at 8:25, the evening of February 21, 1903, to father Joseph Joachim Nin, 23 years old, and to mother Rose Celeste Culmell, 25 years old, at their home on 7, rue du Général Henrion Bertier, Neuilly sur Seine. The midwife was Lucile Marie Anna Mabille, 41 years old. (The spellings of the names reflect the French versions of the Spanish names.)

Interestingly, Rosa’s age is incorrect: she was in fact 31 at this time. Whether this is a clerical error or whether Joaquín and/or Rosa wanted to keep their age difference a secret is pure speculation.

According to Nin biographer Deirdre Bair, Joaquín was not pleased at having a child so early on in his marriage and, perhaps more importantly, his career. He became jealous of the attention Rosa gave her delicate daughter. This seemed to interfere with the performance relationship the couple had…at first Joaquín insisted Rosa perform with him in order to get her away from Anaïs, and then, irrationally, insisted she not perform when he felt Rosa was neglecting both him and Anaïs. From that point forward, Joaquín Nin became a solo performer and Rosa was reduced to a mother who sat in the audience to cheer him.

By the time Anaïs’s brother, Thorvald, was born in Havana in 1905, she was afflicted with typhoid fever, becoming violently ill. Joaquín was repulsed by the sight of his now very thin, sickly daughter and made sure she knew how ugly he found her. By the time Anaïs’s youngest brother, Joaquín, was born in Berlin, the family life had deteriorated to the point of chaos and violence. Beatings were brutal and often, at the hand of the father. The violence between Joaquín Sr. and Rosa intensified to the point where Anaïs feared for her mother’s life (see the introduction to “Prelude to a Symphony—Letters between a father and daughter,” A Café in Space, Vol. 6). By 1913, the family as Anaïs knew it was destroyed when her father abandoned them, and for the rest of her life she would be torn by the loss.

It is also interesting to note that while we readily celebrate Anaïs’s birthday, she rarely refers to it—or to Christmas, New Year’s Eve, or other traditionally notable days—in her adult diary. On Feb. 20, 1925, just before her 22nd birthday, she wrote: “On the eve of my birthday and bowing to tradition, I try to consider thoughtfully the significance of this venerable day—in vain. Dates never agree with my transformations. My real birthday this year was when I read Edith Wharton’s books. My New Year began when I succeeded in having my story run smoothly, when I found a renewed interest in my second book. My holidays are many—every time I go downtown with Hugh, when the agitation of the city, like the quick rhythm of some Spanish danza, makes my heart beat faster. My religious festivals fall on whatever day the sun shines—those are my Mass-going days, when I can pray.”

If you have thoughts to share on this day, Anaïs Nin’s 106th birthday, leave a comment or visit our guestbook.

Anaïs Nin Myth of the Day

February 18, 2009Myth #4: Anaïs Nin was fluent in three languages: French, Spanish, and English.

Fact: When Anaïs Nin’s father, Joaquín Nin, abandoned his family in Arachon, France, in 1913, she, her mother and her two younger brothers went to Barcelona and stayed with Joaquín’s parents. During the year or so they spent in Spain, Anaïs learned her Spanish. When the fatherless family arrived in New York in 1914, French was the spoken language at home. Although Anaïs’s mother, Rosa, was fluent in English (as well as Spanish and French), she had determined the family’s “mother tongue” was French. Her philosophy was that since her children would learn English soon enough in school and in their social interactions, and that Spanish would be spoken with their Cuban relatives, the only way to keep the French alive was to speak it exclusively at home. When Anaïs began her diary on the trip to America, it was in French.

Although her English was improving over the next few years, Nin continued her diary writing in French, partly because she longed to retain her identity, and partly because she intended the diary as a long “letter” to her estranged father, who did not know English. As her English grew, her French withered. Her father chastised her for her misuse of words and accent marks, leading Anaïs to close one of her letters with all the accent marks at the end: “Put them where they belong,” she told him. Sometimes Anaïs would transcribe letters to English-speaking friends into her diary, and it was clear that she was better able to express herself with English. She began reading the English-language classics, and by 1920 had switched her diary to English. Her English was by far a better vehicle for her self-expression, but was still a work-in-progress, and would be for years to come.

As Anaïs began to attempt to write fiction in English after returning to Paris in 1925, her young husband, Hugh Guiler, in the name of helping her, criticized her incorrect (as he saw it) use of words, or the use of words that were considered archaic or odd. Later on, Henry Miller would do much the same (see Myth #2).

Consider this passage Miller corrects from “Djuna” in The Winter of Artifice (sometime in the mid-1930s):

“Are you afriad to forget your name and who you are, and where you live? Have you not played with the idea of amnesia, which only meens a somanabulistic condition of the ideal self. The conscince goes to sleep and then the critical self too, and you can walk the streets and act as you please without calms.”

Miller blasts her misspellings, and when he criticizes her use of “calms” for “qualms” he says: “Look it up!!!” He adds: “Bad sentence structure” and “Watch all your ‘ands,’ ‘buts,’ etc. Weakly used!” (See Benjamin Franklin V’s introduction to The Winter of Artifice: a facsimile of the original 1939 Paris edition.)

At times, Nin felt hopeless—she had Guiler and Miller criticizing her English, and she admitted to Miller that writing in French to her father was “like trying to create a river with twigs” (see “Prelude to a Symphony: letters between a father and daughter,” A Café in Space, Vol. 6). Her Spanish at this time was almost non-existent…her father occasionally wrote to her in Spanish, but Anaïs did not respond in kind.

As Nin developed artistically through these trials by fire, her writing became stronger, more economic, and possessed an exotically distinct quality. It is often described as “English written in the French style.” There is no question that Anaïs Nin became one of the most eloquent writers in the English language, and to this day one of the most oft-quoted…but during the transitions between her three languages, arguably caused by her constant resettling, she was fluent in none of them.

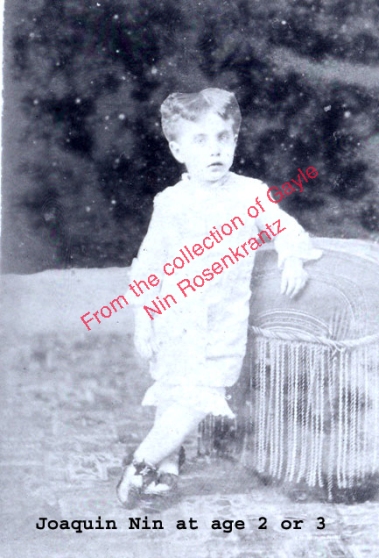

Approaching Anaïs Nin’s 106th birthday: the Spanish and Cuban heritage

February 5, 2009 Here are some details about Anaïs Nin’s Spanish and Cuban relatives. Again, many thanks to Gayle Nin Rosenkrantz, who has cleared up some misinformation and supplied the photo.

Here are some details about Anaïs Nin’s Spanish and Cuban relatives. Again, many thanks to Gayle Nin Rosenkrantz, who has cleared up some misinformation and supplied the photo.

Anaïs Nin’s Spanish grandfather, Joaquín Nin y Tudo, was a military officer stationed in Cuba, and her grandmother, Angela Castellanos y Perdomo, was Cuban by birth. Their son José Joaquín Nin y Castellanos, Anaïs Nin’s father, was born in Cuba on September 29, 1879. Perhaps because being born Cuban was something of a detriment in the eyes of Spanish nobility, Joaquín Nin y Castellanos was baptized in Spain a year after his birth. Since his father decided to stay in Barcelona, Joaquín spent most of his first 21 years there. Although it has been said that he looked down upon his Cuban relatives, referring to them as “peasants,” his Cuban relatives were by far wealthier than the Nins and were also very proud of their heritage. Moreover, when Cuba gained its independence, Joaquín opted for Cuban citizenship.

Joaquín had a natural ability at the piano, studied in Barcelona and gave his first performance there as a teenager. He gave piano lessons, and he apparently seduced one of his female students, whose father threatened him bodily harm. Joaquín fled Spain and set out for Cuba in 1901. According to Deirdre Bair, Anaïs Nin’s biographer, the reason he dropped the “Castellanos” from his name was to distance himself from the disgrace he’d incurred. However, this doesn’t seem to make sense since it was a Nin, not a Castellanos, who got the young girl into trouble. Joaquín Nin’s son, Thorvald, said that his father wanted to keep things simple, so he also dropped the first name, José, and was professionally known as Joaquín Nin from that point on. Another reason to believe that Joaquín valued his Cuban heritage was the fact that it was the Castellanos family who took him in and supported him after fleeing Spain.

Joaquín Nin thought very highly of his father, and dedicated his first performance in Barcelona to him. In 1933, when Joaquín began reacquainting himself with Anaïs after a twenty year estrangement, memories of his father filled his letters to her (a sample of these letters can be read in A Cafe in Space, Vol. 6). However, Anaïs’s memories of her Spanish grandfather were less glowing: she thought him to be a terrifying tyrant. On the other hand, Anaïs remembered her grandmother, Angela, as sweet and kind…in fact, all of the Nin family remembered her that way.

Anaïs Nin: Feminist or not?

January 26, 2009Was Anaïs Nin’s writing feminist in nature? There is a dichotomy in responses. In her article “Feminist Smut (?)” (A Café in Space Vol. 6) scholar Angela Carter makes the statement that one of the works most vilified by feminists—the erotica—is actually feminist. Carter sees the erotica as a writing out of the struggles women had with sexual identity and expression in a patriarchal world. In the same issue, Sarah Burghauser writes that her perception of Nin was swayed by the attacks from feminists who claimed not only was Nin insincere and essentialist, she used the Women’s Movement to “sell books.” Bruce Watson, in his article “Claiming Ownership—Issues in Nin criticism,” takes note of the backlash of feminists directly after the release of Diary I, but he also explains how others have attempted to equate Nin’s style of diary writing to a form of feminist expression, an argument that has taken hold as time goes on.

When the diaries came out during the late sixties and early seventies, at the height of the Women’s Movement, women divided themselves into two distinct camps: those who believed that while Nin was not a typical “bra-burner,” she was a leader in the establishing women as distinct figures with unique gifts and the need for freedom of expression; on the other side were those who felt Nin had betrayed the Women’s Movement by being “too feminine,” i.e., using her womanly charms to attract men, using men to achieve her success.

There was a misconception from the onset: when the original Diary came out in 1966, readers assumed that Nin accomplished everything alone, that there was no man supporting her, that she was a feminine pioneer, especially in the light of the fact she wrote the diary in the 1930s when few women ventured from the kitchen into the world of art, literature, or making a living. When these readers discovered that Nin in fact had a husband who was her financial backbone, not to mention an anchor who gave her the safety net she seemed to be living without, they felt betrayed. “Fraud,” they cried. Some of them attacked Nin at lectures, in print, and in the media, echoes of which resound to this day. The irony is this: had these very readers read editor Gunther Stuhlmann’s introduction, they would have known that Nin indeed was married, and that it was her husband’s wish to not be mentioned in the Diary. So, did Nin mislead her readership in this way? Not if you read the disclaimer.

In this sense, part of the argument against Nin’s feminism doesn’t hold water, but this only one minor aspect of the dispute. There are many other points to argue, but under no circumstances did Nin enter the confrontational or militant, anti-male sector of feminism. Women could not become stronger or freer by acting like men, Nin argued, and using man’s weapons—aggression, intolerance, brutishness—was counterproductive. Despite the rationality of this stance, it seemed to create the strongest resentment of Nin by feminists.

Judging from the arguments made by scholars and feminists, pro and con, the controversy of Nin’s feminist philosophy, or whether she even had one, will continue until the world gets to the point where her vision of sharing what we have to offer as men and women, equal in each other’s eyes, becomes a reality. Are we drawing closer?

Anais Nin’s appearance: yet another facet of her persona

January 18, 2009

Photo: Mario Grut. All rights reserved.

As British scholar Ruth Charnock notes in the upcoming Vol. 6 of A Cafe in Space (due out Feb. 21, 2009), as well as American scholar Sarah Burghauser in Vol. 5, Anais Nin’s appearance had much to do with her public persona. Charnock recalls Evelyn Hinz’s comments that when Nin appeared at lectures, she seemed to come from between the pages of her diary, that the audience felt they were witnessing not only the author of the famed diaries, but the woman who appears in them even though they were written decades earlier. Nin commented on her appearance from time to time in the diary, noting lines about the eyes, the weakness of the neck, but she also noted that her body retained its youth–her breasts were firm, her legs slim and beautiful. At the age of 70 she recorded the fact that she still was desired, that she still inspired love letters. Nin did resort to cosmetic surgery before it became popular to do so…she had a nose alteration early and a facelift much later. But Charnock notes that there is a certain grotesqueness in the older woman’s youthful body, a body that can play tricks on the mind of the observer. Indeed, the photograph accompanying Charnock’s article is of Nin in the 1960s, wearing a miniskirt and go-go boots…a striking contrast with her face. The photograph here was taken in 1960, when Nin was 57, by famed Swedish photographer Mario Grut. The photograph gained notoriety with its unforgiving harshness, leaving little illusion about the fact Anais Nin was in fact not ageless, but starkly human.

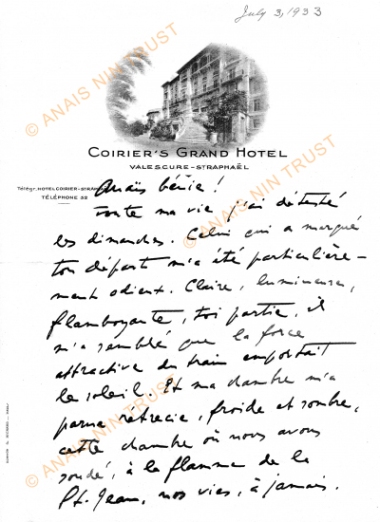

Newly discovered letters to/from Anais Nin and her father

January 15, 2009There has long been speculation on whether Anais Nin in fact had an incestuous affair with her father, in spite of her graphic accounts in her diary (the unexpurgated Incest). Some claim the affair was fabricated, that it was a psychological experiment in which Nin wrote out her desires instead of acting upon them. Others claim Anais was lured into the relationship, and it has been said that it was the other way around. Deirdre Bair mentions in her biography of Nin that all correspondence between the two during this time was destroyed, but recently a sorted, dated collection of letters between Nin and her father have surfaced. Nin did not destroy the letters, as Bair claims, but instead kept a very complete collection in a folder. We have begun to transcribe and translate the letters…the first group appears in Vol. 6 of A Cafe in Space. Do the letters finally answer the question of incest once and for all, or do they simply raise more questions? Each reader has to make his or her own conclusion, which is usual in the world of Anais Nin.

One of the many letters to Anais Nin from her father