Anaïs Nin wrote, “There was once a woman who had one hundred faces. She showed one face to each person, and so it took one hundred men to write her biography.”

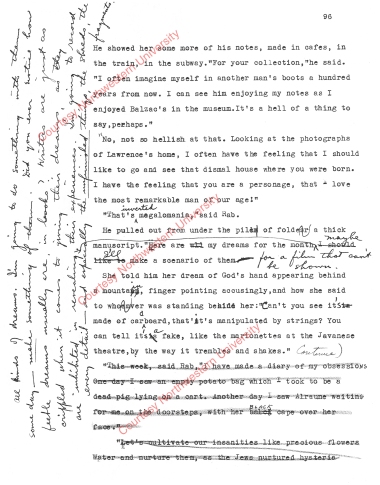

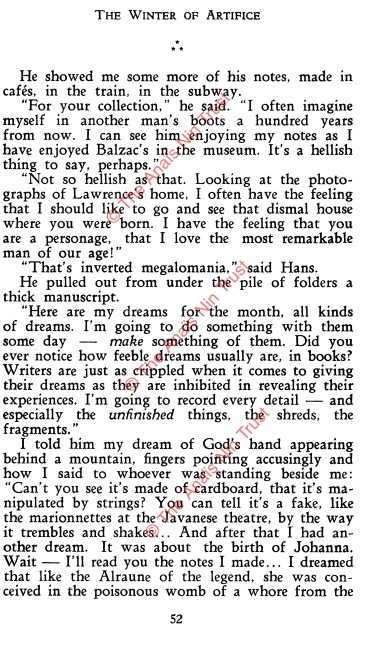

During her lifetime, Anaïs Nin dodged questions that aimed to pin her down, to reveal the details of her life (or lives lived simultaneously). She was vehement about keeping things private, as strange as it sounds considering her life was the source of material for nearly all of her writing. But what was it that she actually presented in her books? She began chronicling her life with her fiction, which was, as she put it, a “distillation” of events that were recorded in her diary (and the diary was often a distillation in itself). Characters were largely based on herself and those in her circle, such as Henry Miller (Hans in “Djuna” from The Winter of Artifice and Jay in later fiction), June Miller (Johanna in “Djuna” and Sabina in The House of Incest and later fiction), Gonzalo More (Rango in “Hilda and Rango” from Little Birds). Yet she often denied her characters were based on real people, caught in a strange predicament: writing out her life but trying to keep it secret. She was often quoted as saying that her motivation for secrecy was to protect the innocent, those who would be hurt should the nature of her many relationships (especially sexual) be exposed.

The publication of Nin’s diaries was a discombobulated process from the very start. First, they had to be “cleaned” of any direct references to her love life, names had to be changed, and entire passages had to be removed if they referred to someone who did not wish to appear in the diary (her husband, Hugh Guiler, for example). The result, then, is not what is popularly perceived as a true “diary.” When one sees the term “diary,” one is conditioned to think “facts,” “dates,” “chronological events,” and “names.” Gunther Stuhlmann, in the introduction to Diary 1 (1931-1934), which was published in 1966 when Nin was 63 years old, expertly states what this “diary” actually is—a “psychological” truth. Apparently, too few people read the introduction and therefore tried to impose a literal truth on writing that was often not. After the 7 volumes of the Diary (which covered the years 1931 to 1974) came the problem of releasing what had been cut out, and what came before it. The childhood and young adult diaries (1914-1931) were released in a more complete form—the editing was not radical; in fact it was marginal. But beginning with the Miller years, Nin’s life had turned about face and became highly sensual, sexual, and consequently deceptive. Suddenly there were numerous affairs (including one with her estranged father), lies to her husband and her lovers, a late-term abortion, betrayals to those who loved her. So a new set of diaries, the so-called Journal of Love series, was released, beginning with Henry and June, after the death of Guiler in 1985.

These “unexpurgated” diaries, especially the second, Incest, caused open rebellion among many of those who’d befriended Nin, or who admired her, because they all felt betrayed—they thought they knew the woman with “one hundred faces.” In 1994, at the Nin conference at Long Island University, Joaquín Nin-Culmell famously walked up to the “friends” table and exclaimed: “You did not know my sister!” in rebuttal to what he considered their “delusion.” A few years later, I had lunch with a group of women who’d known Nin (albeit marginally), and none of them could bring themselves to believe that their beloved Anaïs, the kind and generous woman they knew, was capable of the deeds which appeared in Incest (the father relationship, the abortion). There were those who felt that these events were exploited (if not fabricated) by Rupert Pole (Nin’s California husband and executor) and Gunther Stuhlmann to make a quick buck. In short, after the first two volumes of the Journal of Love were released, there were many bitter and disillusioned people walking around, and the need for someone to sort out the actual facts of Anaïs Nin’s life was apparent. But was it possible? Since then, two biographies (Anaïs: The Erotic Life of Anaïs Nin, by Noel Riley Fitch [1993], and Anaïs Nin: A Biography, by Dierdre Bair [1995]) have been published, but do either give us the whole picture?

Coming soon: an analysis of what has been written so far.